Introducing Lisp

2019-12-01

This post is a basic introduction and broad overview of the Lisp programming language. It prefaces a series that will educate you, the reader, as to what Lisp is, what it does, why it's great, and so on.

Rationale

You might be wondering why I have chosen to discuss Lisp. If you've never heard of it, then you have no idea what it is and what I'm about to spend a few precious weeks writing about. If you have heard of it, chances are what you have heard may have been inaccurate or off-putting. I'll admit it – Lisp can seem a bit weird at first, even to the point where you'd write it off as pointless, unnecessary, or impractical.

Everything above is precisely the reason I'm writing about Lisp. If you're new to it, I want to educate you about it. If you've heard of it, I want to reeducate you, to provide you with a more informed and holistic view. In either case, after reading this series, you should have at least some basic understanding of the what, why, and how of Lisp.

Another question, which perhaps you're not even asking but which I will answer anyway: Why have I chosen to start off what will (hopefully) be a long-running blog with Lisp posts?

It's simple, really. I'm passionate about it.

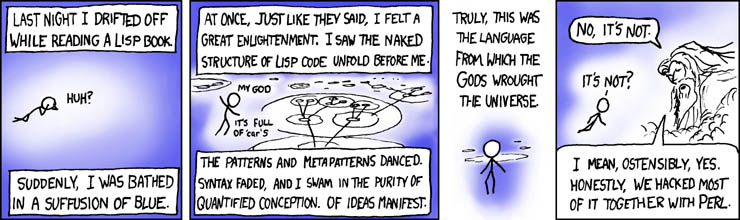

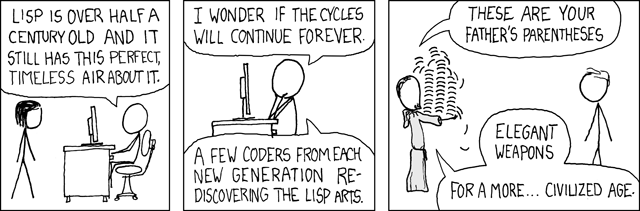

If you look at my recent GitHub projects, you'll see that quite a few of my projects are written in Clojure, an offshoot of Lisp. Surely I must like the language enough to use it time and time again. True, it is possible that some other flashy language will enrapture me soon, but for the time being, Lisp is very exciting to me and many others. And why is that? Well I'll explain most of that later, but the summary is that Lisp allows me to think about and write my code in a way that I find to be clean, elegant, and overall more productive. There are finicky bugs and issues I have run into with other programming languages that I simply don't with Lisp. I spend more time on problem-solving instead of bugfixing. This is nodded to in the following xkcd comics.

We lost the documentation on quantum mechanics. You'll have to decode the regexes yourself.

I've just received word that the Emperor has dissolved the MIT computer science program permanently.

Furthermore, I wish to share this passion with you. It is my hope that, by the end of this series of posts, you will, if not use Lisp, understand its merits and apply some of its principles as you program.

Onto Lisp!

Definition

Any good explanation should begin with some kind of basic definition to serve as context for what is to come. Lisp is a bit of a nuanced language, distanced from more mainstream ones (i.e. the C family, including C, C++, Java, etc.), which necessitates a definition that explains these nuances and their origins.

A Language Family

First things first. Lisp is not a programming language!

"What? How? If it's not a programming language, what is it? And why are you bothering to write about it?" you exclaim with a fervor.

Settle down, I'm not throwing you under the bus.

Lisp is not a programming language; it's something better. It's a family of closely related programming languages dating back to 1958.

Each language serves a unique purpose and bears some distinct and innovative features. These may be built into the language, its execution model, its standard library, or some combination of the three. Here are some examples

- Clojure - a Lisp dialect for the Java ecosystem with a strong focus on immutability and concurrency

- Emacs Lisp - a Lisp dialect for programming and extending the Emacs text editor

- Hy - a Lisp dialect for the Python ecosystem

- Ferret - a Lisp for embedded systems development

However, most if not all Lisps share some defining features, such as those below

- Programs are written as "S-expressions" (short for "symbolic expressions") represented as lists of the form

(function arg-1 arg-2 arg-3) - Lisp languages follow and arguably developed the functional programming paradigm

- Metaprogramming with powerful macro systems - Since Lisp code is written with lists and functions can manipulate lists, Lisp code can manipulate itself

Lisps have come and gone over the years (61 years as of writing, to be exact, demonstrating its continual success). Sure, it might be depressing for a language to fall out of use, but the close relationship of Lisp languages in a family provides an important benefit: learning one Lisp simplifies learning the rest.

This has some important advantages.

For one, if one language falls out of favor, it is not too hard to pick up a new one and start using it. Lisps have many characteristics in common, enabling developers to reference the same repertoire when using different dialects.

Another benefit of Lisp is that different Lisp dialects can specialize for different application domains while retaining the core principles that make Lisp what it is. With mainstream languages, each domain generally requires a new language with its own syntax, semantics, and paradigm, all of which take up precious time and head space to develop skills in. But with Lisp, many core features will remain the same, so there is less cognitive overload in developing for a new domain. Consider the move from web development to low level development – JavaScript and C are very different languages, whereas two Lisps, one for each domain, will have much more in common.

For instance, many Lisp developers use Emacs as their text editor. Emacs can be manipulated with Emacs Lisp, which is very easy to pick up once you already know one Lisp.

Now let's get into what Lisp really is.

LISt Processor

I mentioned this earlier, but Lisp code is written with lists. Lots of lists. Hence its name actually stands for LISt Processor, since Lisp runtimes execute code by processing a series of lists. As such, not only are lists important as core data structures, but they are core to the very nature of Lisp itself. Take a look at the following (interactive!) code sample, written in Clojure.

(println "hello, world!" "goodbye, world!")

Lists are denoted by opening and closing parentheses. When evaluated, the first element is treated as a function, while subsequent elements are treated as arguments. In the above code, we pass the println (print line) function two strings ("hello, world!" and "goodbye, world!"). Voila! The two strings are printed, one after another.

After the printout, nil appears. This is the empty value (equivalent to null in other languages). Here, it's just println's return value.

So lists are function calls. Neat! But you can also treat lists as normal data structures, like in most languages.

(first '(1 2 3))

Here, we grab the first element of the list (1 2 3). The ' prefix essentially forces the list to be treated as a data structure rather than being evaluated as a function call. Then first grabs the first element of the given list, which in this case is 1.

Pretty simple stuff, right?

Well remember how I mentioned macro systems earlier? The fact that lists are, by default, treated as function calls and that functions can manipulate these very same lists allows programmers to define macros that manipulate source code. The following is a very simple and impractical example, but it gets the point across.

(println "Hello" "World")

(eval (butlast '(println "Hello" "World")))

Above, we begin with simply printing out "Hello World". Not too hard to grasp.

The next line is what's interesting. Beginning with the innermost term, we have the list (println "Hello" "World"). Notice it is prefixed with a ', so it will not be evaluated as a function call, at least not yet! Then we use the butlast function to construct a new list that contains every element except the last one. Finally, we use eval, which evaluates a data structure. In this case, the data structure is the list (println "Hello"). When evaluated, println is treated as a function and "Hello" as an argument. So we print out Hello. "World" was dropped out of the code by butlast so it was not printed.

Again, this is a very rudimentary and unrealistic example, but it shows how code can be manipulated as data before finally being evaluated. This property of Lisp is known as homoiconicity – code and data have the same representation so each can be treated as the other. Code is data and data is code, which lends to an incredibly powerful macro system.

Lisp in the Real World

Alright, enough of that. You'll get some more practice with how to use Lisp in future posts. For now, let's focus on Lisp's origins and it's importance to computer science, both theoretical and practical.

Origins

Lisp originated at M.I.T. in John McCarthy's influential paper Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I. The name is quite a mouthful, but the paper essentially defined Lisp, the rationale behind it, and some of its implications.

Lisp was created by M.I.T.'s Artificial Intelligence team to implement a proposed system called Advice Taker, which would receive information and instructions and demonstrate some level of common sense and logical reasoning. To achieve these goals, Lisp would need to be able to manipulate expressions representing inputs to Advice Taker. This was achieved in part via Lisp's support for self-modifying code. Much artificial intelligence research over the coming decades was fueled by Lisp, with many natural language processing programs written in it.

Lisp was also introduced as a more practical notation for lambda calculus, a Turing-complete model of computation. Lambda calculus was introduced in the 1930s by Alonzo Church and approaches computation in a manner that is built around functions and binding names to values. Functional programming languages take many concepts both from Lisp and lambda calculus.

Impact and Implications

Lisp is a fully Turing-complete language built with a remarkably small syntax and set of operations (as you will see later, even things like function definitions aren't very fancy – they're written as lists!). This lends to many programmers calling it an elegant language. It does not take up much head space and it's very easy to read, since only a few core concepts and language features have to be learned in order to understand any Lisp code. This also makes it trivial for you to make your own Lisp! Granted, many Lisp languages have added additional features on top of the original proposal, but they are very careful to avoid introducing too many new concepts and many of these additions were arguably necessary for practical use. For instance, the original Lisp proposal lacked explicit support for even basic integers (there were ways to hack it in there, but adding them outright was certainly far easier). Do not misinterpret this to mean that Lisp is simple in what it can do, hoewver – its syntax may be simple but it is an immensely powerful language.

The REPL

Lisp's runtime strategy is also very important. Because of Lisp's eval function, shown above, it is trivial to implement a Read – Eval – Print Loop (a REPL), where users can type in code and have it evaluated instantly. The REPL program flow looks like the following

Read – Eval – Print Loop Program Flow

- The user is prompted to enter some Lisp code

- Lisp code is passed to the program as text

- The Lisp reader parses the text into Lisp data structures

- The data structures are passed to the evaluator, which evaluates the structures

- The final evaluated value is displayed to the user

- The program loops, beginning again at step 1

Lisp's REPL and macro system demonstrate that Lisp makes no difference between compile-time and runtime. New code can be compiled and evaluated during runtime, and, during compile time, code can be run to produce new code to compile and evaluate. The REPL system also makes it extremely easy to prototype code. There is no lengthy compilation phase or setup required to try new code – just type it in and see if it works. If it doesn't, try again until you are satisfied. Many popular programming languages today feature REPL systems (see repl.it, for instance) that you can thank Lisp and John McCarthy for. The ability to read and analyze new code during runtime also relates back to Lisp's roots with Advice Taker, since it would need to analyze user input, produce code, and evaluate it.

Functional Programming

Finally, Lisp introduced the functional programming paradigm, which is still going strong today and becoming increasingly popular among developers. Functional programming is born out of mathematics and bears a number of resemblences. For instance, variables aren't usually variable in math; that is, they are immutable. Functional programming encourages the use of immutable values rather than mutable variables and mutating state. Pure functions are also heavily encouraged. These functions derive their return values solely from their arguments (i.e. no global state affects them) and do not result in any side-effects (i.e. their only purpose is producing a return value). Such functions are easier to test and use in a variety of situations, since they are truly isolated from their environments and don't require anything to be set up besides their input arguments. There are some other neat features, such as referential transparency or memoization, but I won't go into detail about them here.

One other core feature of functional programming languages is higher-order functions, which are functions that receive functions as arguments and/or return them as values. In Lisp, this is enabled in part by homoiconicity. Since functions are code and code is data and functions can receive and return data, they can receive and return functions. Again, Lisp is a very simple language but it really has a lot of features that make it incredibly powerful.

One very important higher-order-function is called apply, which takes a function and a list of arguments and applies (invokes, essentially) the function to the arguments. See the following example with addition below.

(println (apply + '(1 2 3)))

;; This is equivalent to

(println (+ 1 2 3))

Above, the addition function (+) is applied to the arguments 1, 2, and 3, producing 6, the sum of the three numbers. apply is a higher-order function because it takes a function as its first argument. apply is very important for the Lisp execution model. When a list such as (+ 1 2 3) is evaluated, the evaluator actually invokes apply -- + is the function and (1 2 3) is the list of arguments.

You'll see in future posts how important higher-order functions are for writing code that is clearer and more elegant. (there's that word again!)

Conclusion

There are many, many, many more impacts that Lisp has had across the computer science spectrum, too many to put into one blog post, but the ones I've listed are arguably some of the most important. Hopefully I have sparked enough interest in you that you will seek these things out on your own, because Lisp truly is a magnificent thing.

In the next post, we will explore how to write Lisp code and how to think about writing Lisp code, because chances are it's different from how you've written code in the past. Stay tuned!

Further Reading

If you're interested in learning more about Lisp, I suggest looking at the following resources

- Clojure for the Brave and True - a free ebook that teaches readers how to use Clojure

- Paul Graham's writings on Lisp